It’s almost never “just me”. Even when we “dare to bare” our hearts on social media (a perilous adventure), where this plaintive question seems to pop up frequently. Living in a cosmos of other beings, it’s almost always something more, ultimately so likely that it’s safe to make it a default setting on our outlooks. (Sometimes, however, you do need to choose the best audience to share it with. Many humans understand much less of such things than most trees, for instance. Looking for solidarity and confirmation? Share it with a tree first!) Encounters everywhere, reminding us, calling to us, engaging us to look beyond “just me”.

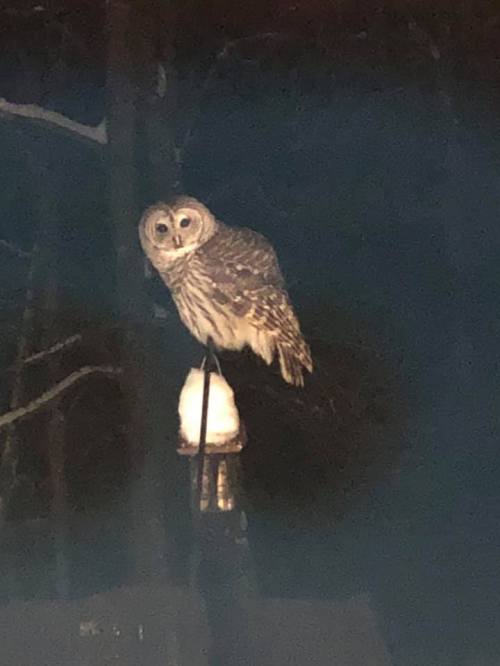

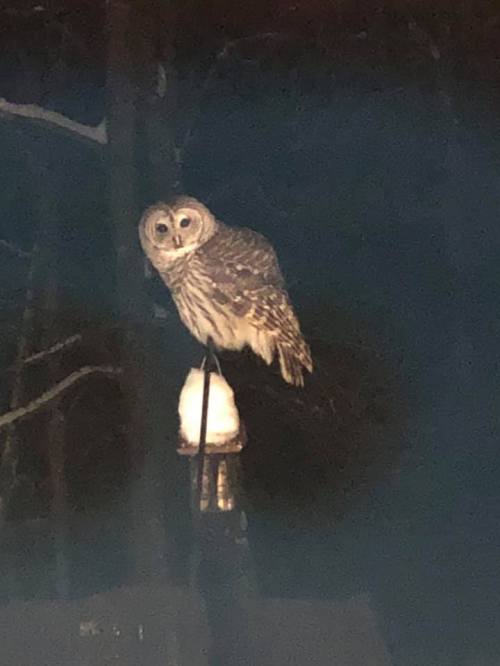

Here’s a night visitor to a Vermont Druid in the northern part of the state — a lovely barred owl (Strix varia).

Barred owl, 15 Feb. 2019. Photo courtesy Sue S.

Wherever we are, whatever we’re doing, it’s always about more than just me.

Owl says so!

/|\ /|\ /|\

I’ve mentioned before on this blog that I practice two distinct spiritual paths. One of the teachings on the other path concerns waking dreams. “A waking dream is something that happens in the outer, everyday life that has spiritual significance”, writes one of my guides on that path. And the crucial point, for me, is that I can perceive that significance. Or miss it. Or call it coincidence, or something else.

In her post “The Reality of Omens“, Druid Life blogger and author Nimue Brown writes,

When looking for omens in the world around us, it is necessary to consider how reality works in the first place. One of the things I have rejected outright is that other autonomous beings could show up in my life as messages from spirit – because the idea that a hare, a sparrowhawk, or some other attention grabbing thing could have its day messed about purely to try and give me a sign, is profoundly uncomfortable to me. I have something of an animist outlook, and I do not think the universe is *that* into me.

Brown’s caveat rings true — we can safely pare the human ego down, without fear it will crumble and disappear. Unlike the average toddler, most adults handle reasonably well the discovery that they’re not actually the center of universe.

But as a fellow semi-animist, I’d not separate “spirit” from what you and I and other things are doing every day. “Spirit” isn’t a thing that stands apart from what it inhabits — it’s not a bearded Jehovah lounging in the heavens, lording it over the rest of the cosmos, twitching the puppet-strings to get his way with us. Spirit permeates things — it’s what peeks out when you look in the eyes of a dog or bird or bug, or into the heart of a flower. It’s what gives waves their curl, or cumulus clouds their cotton-like billow, or your jogging neighbor the will to keep at her four-mile routine, in spite of December sleet. Spirit makes things thing-ly — how else can I detect its presence? Ever seen it hanging out all by itself? Pay attention and I can notice now more, now less. But never apart from the things it’s been doing all along, like you and me and the grass growing tall in the back lawn where I haven’t mowed it at all this year.

The skies cloud over, the temperature drops and a wind kicks up. Is it an “omen”? No — but these things do carry meaning to anyone paying attention. It’s probably going to rain soon. That particular kind of omen we call a “no-brainer” (though humans still manage daily to ignore even obvious omens). As part of the universe where a local storm is brewing, I can pick up on other things spirit is doing, or I can ignore them. The universe “isn’t that into me”, but it is in fact *in* me, and in you too, and we’re both in it.

So I prefer to see “omens” and “signs” as friends visiting. Spirit is simply flowing. One of its flows is you, another is me, a third is the car pulling into the driveway with S. at the wheel, “just stopping by” on her way home after shopping. If I gain insight or wisdom or a nudge to do something, or a burst of gratitude from that visit, then I’m paying attention in some way, and I’m being me, with my own unique responses to what spirit’s always doing all around and in me.

Rather than worrying overmuch about whether it was a sign or an omen or simply another wave in the ocean of spirit manifesting everywhere and everything, why not measure its effects? Is my life deeper, richer? Are the lives of others made richer and deeper? Is that enough, without checking the box labeled “omen” or “not omen”?

But what of the autonomy Brown names as part of her animist understanding of the uni-verse, the “one-turning”?

The idea that “other autonomous beings could show up in my life as messages from spirit – because the idea that a hare, a sparrowhawk, or some other attention grabbing thing could have its day messed about purely to try and give me a sign, is profoundly uncomfortable to me”, she notes.

But she and the many other beings in her life can be and are many things at once. And so are you and I. Like spirit in us and all around, I am many things at once. I am not “purely” anything, but delightfully mongrel. I’m an incarnate human, and also a Vermonter, a husband, a blogger, an aging white male, a person alive in the 21st century, an American, the son of two parents who both lost fathers while still in their single-digit years. I am a manifestation of spirit, a homeowner, a Druid, a teacher, a conlanger, a portal of Mystery, and so on. (Maybe the problem isn’t labels by themselves, but that we never use nearly enough of them. Scatter them like seed. Each is — not a limit — a possibility.) Each of these features opens access points for spirit to reach other beings, while leaving me with the same freedom as other “autonomous beings”. Spirit does “overlap” and “interconnection” really well.

My individuality and freedom are what spirit uses to connect with all other free and individual things. Spirit as the whole, the universe, seems to “love” individuals — that’s why there are many of us, rather than just two or three. Spirit as “one thing” interconnects and links all things, all these other “one things”.

So when a crow flies overhead while I’m checking the squashes in the garden, the crow is a crow and a friend visiting and a reminder, if I’m listening, of animal intelligence and and and. Its appearance and my awareness meet, for whatever comes from that meeting. Omen, sign, friend visiting, reminder of crow wisdom to fly over things before I decide to land on them, spirit guide — because spirit is always sparking the beings it pervades — to eat, fight, flee, love, mate, birth young, flower, fruit, grow old, die, return, become, become.

And the crow also discovers and learns something. Here’s a human that does not aim a gun at me as I fly over. Here is a water supply, a pond I can drink from. Here are trees to roost in, good cawing branches to talk to the rest of the flock, food sources to peck at in the scraps and compostables that get put out almost daily. And a hundred other crow things I don’t know about, without shapeshifting to Crow, or crow to me.

Brown goes on to make a key observation about our attention:

I can however read something into my behaviour at this point. I was in the right place at the right time, and I think that tells me something about my relationship with the flow. I take exciting nature encounters as good omens not because I think nature is bringing me a special message, but because it means I was in just the right place, at exactly the right time, looking the right way and paying attention. That in turn means I am in tune, and would seem to bode well for anything else I’m doing.

I simply take “encounter” as “message”. Humans are meaning-makers — it’s what we do. Any omen is an amen, an awen, a chance, a doorway. Will I walk through it? Or will I see how spirit walks through it — to me and to everyone and everything else? And as these things happen, can I catch the Song that is always singing, just at the borders of hearing?

/|\ /|\ /|\

Article in today’s New York Times: “What does it mean to be human?” touches on some of these matters.

A bald-faced hornet up close

Dolichovespula maculata is the resplendent Latin name of a North American insect variously called the bald-faced hornet (BFH after this), the blackjacket, or the bull wasp. “Long wasp spotted” is one literal translation of the Latin (the Im-maculate Conception was “spotless”), and captures well enough their appearance. They’re bigger than most wasps and hornets in the U.S., with a temperament to match. I didn’t take the pic of this brisk specimen to the right (though the larger pics below are mine). The BFH defends its nest vigorously if approached too closely or disturbed.

A short side note: childhood stings, and a love of honey and a relatively bug-free outdoors, taught me a healthy respect and appreciation for bees and wasps, and I’ve learned more about them over the years, some of it firsthand. Most wasps and bees are beneficial, of course, wasps in particular often feeding on insect pests. We’ve had a wetter summer than most this year here in Vermont. Normally that would bring hordes of insects, but we’ve had markedly fewer mosquitos and other pests this summer than any year since we’ve moved here. And the hornets get the credit — we’ve watched them bring back insect after insect to the nest.

The vital honeybees, major pollinators and crucial to many human plant foods, continue to face sharp declines around the world from causes that still aren’t competely understood, and they need our protection. As a U.S. Dept. of Agriculture bluntly puts it, under the heading “Why Should The Public Care about What Happens to Honeybees,” “About one mouthful in three in our diet directly or indirectly benefits from honey bee pollination.” Their troubling decline is thus not a small problem. (You can read about one Druid’s adventures in beekeeping here at the fine blog The Druid’s Garden.)

Mud-dauber wasp nest

We’ve been in our Vermont house since winter 2008, and we’ve co-existed well enough with bumblebees, honeybees, yellowjackets and the more familiar (to us) mud-dauber wasps, which, with a ready supply of mud from our pond, often build their tubular homes above the same back door. They’re also more placid species; we eye each other when either my wife or I go out the back door, or hang or retrieve laundry. Hello, busy people. We come in peace. Carry on, carry on.

It’s important to note here that neither of us is allergic to bees or wasps — an allergy would make this a very different post. Occasionally one or two wasps buzz around our heads, investigating. Once or twice one landed on our hair or an arm or face for few seconds, then flew off again. No stings. We’ve heard stories from neighbors of BFHs landing on a person, plucking off an insect about to bite, and flying off. They’re definitely not timid.

This summer, after we returned from our 7-week cross-country road trip, not one or even two but three BFH nests loomed under our eaves. It was our first encounter “up close and personal” with this species. The BFH nest below is approximately football- or coconut-sized, and much larger ones, housing 400 or 500 or more wasps, have been reported. (The papery exterior shields a series of combs that resemble a beehive’s, helping balance out temperature fluctuations. We’ve had several 24-hour periods recently ranging from 45 at night to 90 during the day.) On the windowless and doorless north side of our house, a nest would hang away from foot traffic,and possibly escape our notice for days or weeks. One of the two other BFH nests hangs from the eaves over our bedroom window, but that has a good screen and tight-fitting crank-out windows.

One of the bald-faced hornet nests under our eaves

This nest, however, hangs just left of one of our back doors, right next to our clothesline. So far, we’re following a policy of “wait and see.”

Bald-faced hornets don’t (yet) winter over in the Northeast. New queens born in the autumn typically survive underground, while workers die off. Everything we’ve heard about BFHs indicates they also don’t return to an old nest the next year. A lot of work for a single year! Just to be safe, however, we’ll remove the nests late this fall — after several good hard frosts.

too close to a door …

Treating the eaves early next spring with Ivory soap as a natural repellent will be our first follow-up. We’ve heard that painting the eaves sky-blue has also worked for some home-owners in southern states, where this hornet is more common. With global climate changes, we’ll probably continue to see more of them here in the north.

Peaceful co-existence is our goal. Meditation and inner conversations with the wasps, thanking them for keeping down the pests, but asking them not to nest on our house, is another equally important remedy I’m now learning and practicing.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: bald-faced hornet close-up; mud-dauber wasp nest.