Ritual Language and the Case of Latin

Many spiritual and religious traditions feature a special language used for ritual purposes. The most visible example in the West is Latin. The Latin Mass remains popular, and though the mid-1960s reforms of Vatican II allowed the use of local vernacular languages for worship, they never prohibited Latin. For some Catholics, the use of vernacular reduced the mystery, the beauty and ultimately, in some sense, the sacredness of the rites. If you visit an Orthodox Christian or Jewish service, you may encounter other languages. Within an hour’s drive of my house in southern Vermont, you can encounter Greek, Hebrew, Russian, Arabic and Tibetan used in prayer and ritual.

Language as Sacrament

The heightened language characteristic of ritual, such as prayer and chant, can be a powerful shaper of consciousness. The 5-minute Vedic Sanskrit video below can begin to approximate for one watching it a worship experience of sound and image and sensory engagement that transcends mere linguistic meaning. The rhythmic chanting, the ritual fire, the sacrificial gathering, the flowers and other sacred offerings, the memory of past rituals, the complex network of many kinds of meaning all join to form a potentially powerful ritual experience. What the ritual “means” is only partly mediated by the significance of the words. Language used in ritual in such ways transcends verbal meaning and becomes Word — sacrament as language, language as sacrament — a way of manifesting, expressing, reaching, participating in the holy.

And depending on your age and attention at the time, you may recall the renewed popularity of Gregorian chant starting two decades ago in 1994, starting with the simply-titled Chant, a collection by a group of Benedictines.

And depending on your age and attention at the time, you may recall the renewed popularity of Gregorian chant starting two decades ago in 1994, starting with the simply-titled Chant, a collection by a group of Benedictines.

Issues with Ritual Language

One great challenge is to keep ritual and worship accessible. Does the experience of mystery and holiness need, or benefit from, the aid of a special ritual language? Do mystery and holiness deserve such language as one sign of respect we can offer? Should we expect to learn a new language, or special form of our own language, as part of our dedication and worship? Is hearing and being sacramentally influenced by the language enough, even if we don’t “understand” it? These aren’t always easy questions to answer.

“The King’s English”

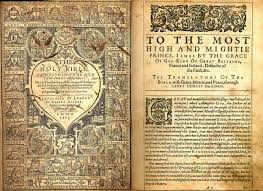

For English-speaking Christians and for educated speakers of English in general, the King James Bible* continues to exert remarkable influence more than 400 years after its publication in 1611. What is now the early modern English grammar and vocabulary of Elizabethan England, in the minds of many, contribute to the “majesty of the language,” setting it apart from daily speech in powerful and useful ways. Think of the Lord’s Prayer, with its “thy” and “thine” and “lead us not”: the rhythms of liturgical — in this case, older — English are part of modern Christian worship for many, though more recent translations have also made their way into common use. A surprising number of people make decisions on which religious community to join on the basis of what language(s) are, or aren’t, used in worship.

For English-speaking Christians and for educated speakers of English in general, the King James Bible* continues to exert remarkable influence more than 400 years after its publication in 1611. What is now the early modern English grammar and vocabulary of Elizabethan England, in the minds of many, contribute to the “majesty of the language,” setting it apart from daily speech in powerful and useful ways. Think of the Lord’s Prayer, with its “thy” and “thine” and “lead us not”: the rhythms of liturgical — in this case, older — English are part of modern Christian worship for many, though more recent translations have also made their way into common use. A surprising number of people make decisions on which religious community to join on the basis of what language(s) are, or aren’t, used in worship.

Druid and Pagan Practice

When it comes to Druid practice (and Pagan practice more generally), attitudes toward special language, like attitudes towards much else, vary considerably. Some find anything that excludes full participation in ritual to be an unnecessary obstacle to be avoided. Of course, the same argument can be made for almost any aspect of Druid practice, or spiritual practice in general. Does the form of any rite inevitably exclude, if it doesn’t speak to all potential participants? If I consider my individual practice, it thrives in part because of improvisation, personal preference and spontaneity. It’s tailor-made for me, open to inspiration at the moment, though still shaped by group experience and the forms of OBOD ritual I have both studied and participated in. Is that exclusionary?

Ritual Primers

Unless they’re Catholic or particularly “high”-church Anglican/Episcopalian, many Westerners, including aspiring Druids, are often unacquainted with ritual. What is it? Why do it? How should or can you do it? What options are there? ADF offers some helpful guidance about ritual more generally in their Druid Ritual Primer page. The observations there are well worth reflecting on, if only to clarify your own sensibility and ideas. To sum up the first part all too quickly: Anyone can worship without clergy. That said, clergy often are the ones who show up! In a world of time and space, ritual has basic limits, like size and start time. Ignore them and the ritual fails, at least for you. Change, even or especially in ritual, is good and healthy. However, “With all this change everyone must still be on the same sheet of music.” As with so much else, what you get from ritual depends on what you give. And finally, people can and will make mistakes. In other words, there’s no “perfect” ritual — or perfect ritualists, either.

(Re)Inventing Ritual Wheels

Let me cite another specific example for illustration, to get at some of these issues in a slightly different way. In the recent Druidcast 82 interview, host Damh the Bard interviews OBOD’s Chosen Chief, Philip Carr-Gomm, who notes that some OBOD-trained Druids seem compelled to write their own liturgies rather than use OBOD rites and language. While he notes that “hiving off” from an existing group is natural and healthy, he asks why we shouldn’t retain beautiful language where it already exists. He also observes that Druidry appeals to many because it coincides with a widespread human tendency in this present period to seek out simplicity. This quest for simplicity has ritual consequences, one of which is that such Druidry can also help to heal the Pagan and Non-Pagan divide by not excluding the Christian Druid or Buddhist Druid, who can join rituals and rub shoulders with their “hard polytheist” and atheist brothers and sisters. (Yes, more exclusionary forms of Druidry do exist, as they do in any human endeavor, but thankfully they aren’t the mainstream.)

About this attitude towards what in other posts I’ve termed OGRELD, a belief in “One Genuine Real Live Druidry,” Carr-Gomm notes, “The idea that you can’t mix practices from different sources or traditions comes from an erroneous idea of purity.” Yes, we should be mindful of cultural appropriation. Of course, as he continues, “Every path is a mixture already … To quote Ronald Hutton, mention purity and ‘you can hear the sound of jackboots and smell the disinfectant.'” An obsession with that elusive One Genuine Real Live Whatever often misses present possibilities for some mythical, fundamentalist Other-time Neverland and Perfect Practice Pleasing to The Powers-That-Be. That said, “there are certain combinations that don’t work.” But these are better found out in practice than prescribed (or proscribed) up front, out of dogma rather than experience. In Druidry there’s a “recognition that there is an essence that we share,” which includes a common core of practices and values.

As a result, to give another instance, Carr-Gomm says, “If you take Druidry and Wicca, some people love to combine them and find they fit rather well together,” resulting in practices like Druidcraft. After all, boxes are for things, not people. Damh the Bard concurs at that point in the interview, asserting that, “To say you can’t [mix or combine elements] is a fake boundary.”

Yet facing this openness and Universalist tendency in much modern Druidry is the challenge of particularity. When I practice Druidry, it’s my experience last week, yesterday and tomorrow of the smell of sage smoke, the taste of mead, wine or apple juice, the sounds of drums, song, chant, the feel of wind or sun or rain on my face, the presence of others or Others, Spirit, awen, the god(s) in the rite. The Druid order ADF, after all, is named Ár nDraíocht Féin — the three initials often rendered in English as “A Druid Fellowship” but literally meaning “Our Own Druidry” in Gaelic.

A Human Undersong

Where to go from here? Carr-Gomm notes what Henry David Thoreau called an “undersong” inside all of us, underlying experience. “We sense intuitively that there’s this undersong,” says Carr-Gomm. “It’s your song, inside you. The Order and the course and the trainings [of groups like OBOD] — it’s all about helping you to find that song. It’s universal.” As humans we usually strive to increase such access-points to the universal whenever historical, political and cultural conditions are favorable, as they have been for the last several decades in the West.

Paradoxes of Particularity

Yet the point remains that each of us finds such access in the particulars of our experience. (Christians call it the “scandal of particularity”; in their case, the difficulty of their doctrine that one being, Jesus, is the sole saviour for all people — the single manifestation of the divine available to us.**) And the use of heightened ritual language can be one of those “particulars,” a doorway that can also admittedly exclude, an especially powerful access point, because even ordinary language mediates so much human reality. We quite literally say who and what we are. The stroke victim who cannot speak or speaks only with difficulty, the aphasic, the abused and isolated child who never acquires language beyond rudimentary words or gestures, the foreigner who never learns the local tongue — all demonstrate the degree to which the presence or absence of language enfolds us in or excludes us from human community and culture. And that includes spirituality, where — side by side with art and music — we are at our most human in every sense.

In the second post in this series, I’ll shift modes, moving from the context I’ve begun to outline here, and look at some specific candidates for a DRL — a Druidic Ritual Language.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: Tridentine Mass; OBOD Star and Stone Fellowship rite.

*Go here for a higher-resolution image of the title page of the first King James Bible pictured above.

**In a 2012 post, Patheos blogger Tim Suttle quotes Franciscan friar and Father Richard Rohr at length on the force of particularity in a Christian context. If Christian imagery and language still work for you at all, you may find his words useful and inspiring. Wonder is at the heart of it. Here Rohr talks about Christmas, incarnation and access to the divine in Christian terms, but pointing to an encounter with the holy — the transforming experience behind why people seek out the holy in the first place:

A human woman is the mother of God, and God is the son of a human mother!

Do we have any idea what this sentence means, or what it might imply? Is it really true? If it is, then we are living in an entirely different universe than we imagine, or even can imagine. If the major division between Creator and creature can be overcome, then all others can be overcome too. To paraphrase Oswald Chambers “this is a truth that dumbly struggles in us for utterance!” It is too much to be true and too good to be true. So we can only resort to metaphors, images, poets, music, and artists of every stripe.

I have long felt that Christmas is a feast which is largely celebrating humanity’s unconscious desire and goal. Its meaning is too much for the rational mind to process, so God graciously puts this Big Truth on a small stage so that we can wrap our mind and heart around it over time. No philosopher would dare to imagine “the materialization of God,” so we are just presented with a very human image of a poor woman and her husband with a newly born child. (I am told that the Madonna is by far the most painted image in Western civilization. It heals all mothers and all children of mothers, if we can only look deeply and softly.)

Pope Benedict, who addressed 250 artists in the Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo’s half-naked and often grotesque images, said quite brilliantly, “An essential function of genuine beauty is that it gives humanity a healthy shock!” And then he went on to quote Simone Weil who said that “Beauty is the experimental proof that incarnation is in fact possible.” Today is our beautiful feast of a possible and even probable Incarnation!

If there is one moment of beauty, then beauty can indeed exist on this earth. If there is one true moment of full Incarnation, then why not Incarnation everywhere? The beauty of this day is enough healthy shock for a lifetime, which leaves us all dumbly struggling for utterance.

Updated (minor editing) 1 April 2014